This Thesis Paper was originally written as a capstone project while I was a student at New Mexico School of Massage, May 2023. It is my most comprehensive, in-depth explanation of Polyvagal Theory, the Autonomic Nervous System, Trauma, and a Bodywork Therapy approach to address these.

Introduction

In early 1993, I moved from Santa Fe, NM to Tucson, AZ shortly after completing a 900-hour certification program in Polarity and allied therapies. After opening my bodywork practice I very quickly found that many of my clients were dealing with extreme early-life traumas, including incest, and devastating physical and emotional abuse. As a newly minted therapist, I recognized that I was way out of my depths with regard to my training and life experience. My polarity certification program included body-center counseling, however, back then that did not encompass healing approaches to trauma. The whole field of body-centered, non-relive trauma therapy was in its infancy at that time.

Those early sessions changed the trajectory of my life and practice. It was the catalyst for me to train extensively in both hands-on and verbal trauma modalities that were growing out of the brand-new Polyvagal Theory (PVT) of the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS). Over the years much has been written on the application of PVT within verbal therapies, however, its application and use in the fields of body-centered therapies has been extremely limited.

Verbal, somatic or body-centered, non-relive trauma therapies such as Peter Levine’s Somatic Experiencing (SE) have become incorporated into both Polarity (PT) and Biodynamic CranioSacral Therapy (BCST) at a fundamental level. SE and other trauma therapies like Eye Movement Desensitization Repatterning (EMDR), Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT) aka. Tapping, and Holographic Memory Resolution (HMR) have evolved over that same period in their understanding and treatment of trauma, as have mainstream clinical psychotherapy and psychology. The proliferation of non-relive trauma systems is due in large part to the groundbreaking research and development of Dr. Stephen Poges’ Polyvagal Theory which is a foundational component in my understanding and approach to healing.

Over the years I developed my own unique application of PVT, based in large part on polarity and various subtle osteopathic (manual therapy) approaches. In the intervening years, I have amassed extensive anecdotal clinical experience in this area from a fundamentally Energy- or Consciousness-based understanding of the interconnectedness of all aspects of the body-mind system (BMS).

Before going further there are several fundamental terms that need to be defined as they will be used repeatedly and underly this theory, especially in relation to bodywork. They are, Trauma and Felt-Sense.

Trauma

People often think that if they weren’t in a car accident, been to war, or didn’t get assaulted they haven’t been traumatized. It is important to recognize that trauma is not ‘what happened’ it’s how we ‘perceive’ what happened. It is a moment or period of time where we couldn’t handle what was occurring. Sometimes it’s a response to something ‘bad’ that happened—we got hit and couldn’t defend ourselves, other times it’s in response to something ‘good’ that did not happen—we REALLY needed a hug in that moment, but no one was there to comfort and reassure us.

Simply put trauma or overwhelm happens when an individual or physiological system(s) cannot process/handle/integrate what is happening in that moment so it holds on to and defers processing that for a later time. The system has been placed into EXTREME distress and the message to one’s self is often “Oh my God I’m going to die!” To do this the BMS enters a self-induced trance of perpetual ‘now’ where it encodes a multiscensory holgraphic fragment of the traumatic event(s) for later processing, at a time when its very existence is not under imminent threat. Emerging trauma research indicates that we are all alive today precisely because of our ‘built-in’ ability to freeze and store memory: to disassociate from our pain, isolate that moment internally and walk away. This paper will begin to explore the far-reaching implications of trauma to our BMS, the insights that Polyvagal Theory (PVT) brings to understanding this phenomenon, its application in verbal therapies, and a new hypothetical model for applying PVT and trauma recovery to bodywork/therapeutic touch.

Definition of Trauma

“A ‘trauma’ is a spontaneous state of self-hypnosis, an altered state of consciousness which encodes state-bound problems and symptoms (Cheek, 1981). Hypnosis occurs spontaneously at times of stress and serves to contain the experience to prevent the subject from becoming overwhelmed. Psychological shocks and traumatic events are psycho-neuro-physiological dissociations and often result in ‘traumatic amnesia’ or ‘delayed recall.’ This amnesia may be resolved by ‘inner resynthesis.’ (Erickson, 1948/1980). The encoding of trauma in the nerve cells of the body is facilitated by the limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary system and exercises a profound influence on the functioning of the autonomic nervous system, the endocrine system, and the immune system (Selye, 1976).

… A trauma is a moment when we utilize our creative resources of mind to ‘pause’ our space-time perceptions to prevent overwhelm to the psyche. The resolution of our traumas, therefore, requires that we address these Powerful encoded moments and states of consciousness.” (Baum, 1997)

Further insight is provided by Sigmund Freud, who described trauma as “a breach in the protective barrier against overstimulation, leading to overwhelming feelings of helplessness.”

Felt-Sense

Felt-Sense is a term that also emerged from recent developments in somatic psychology. Typically, when speaking about our life, we focus on one of two things: our thoughts or our feelings. Our thoughts are connected to the story of our lives; what happened, when it happened, and who did what to whom. Our feelings, on the other hand, are the emotions we attach to that story: happy, angry, sad, or afraid.

The third factor, that most don’t consider or even know exists, is our ‘Felt-Sense’, which is how we experience all of life, particularly our thoughts, and feelings, in our bodies. We so often live in our heads, that many have little to no conscious body awareness. We don’t pay attention to any of our body signals unless they’re screaming at us.

“FELT SENSES ARE paradoxical. In a way they are always there, but since we rarely notice them, they are also not there. When we first bring attention into the body and sense for “something”, we may notice nothing at all. Or we may sense that something is present in a bodily felt way, but it is vague, subtle, murky. In learning to find the felt sense, we have to learn to differentiate it from more common modes of experience: physical sensations, thoughts, and emotions.”

“… felt senses are different from the common emotions that … have names like anger, fear, happiness, and sadness. Nonetheless, felt senses can be described with words, if instead of using nouns we use adjectives.” (Rome, 2014)

In general, what we classify as ‘good’ or ‘positive emotions’ tend to be accompanied by an uplifting, expansive, and pleasant sensation in our bodies; while ‘negative feelings’ have a sense of contraction and downward motion, or else they pull at us in multiple directions at once, or we experience an inner activation without release, like an intense static charge. These Felt-Sense experiences are extensions of our afferent nerve receptors reporting to our central nervous system on our internal body sensations, physiological movement (organ motilities), and the state of our ANS. Felt-Sense is central in this context as it reports back to our mind our Autonomic state.

“To ask how the mind communicates with the body, or how the body communicates with the mind assumes that the two are separate entities. My experience has shown me that they are a single unit. The body is not just a reflection of the personality; it is the personality.

Therefore mind-body awarenesses are two sides of the same coin, different aspects of the same spectrum, immutably joined, inseparable, connected, influencing, and communicating constantly. Myofascial release techniques and myofascial unwinding allow for the complete communication necessary for healing and true growth. I believe that the body remembers everything that ever happened to it.” (Barnes, 1990)

Traditional ANS Model

The Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) is the central component of the neuro-endocrine-immune complex that is tasked with our survival. The neural aspect, the ANS is a component of the Peripheral Nervous System that regulates involuntary physiological processes including heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, digestion, and sexual arousal. The Peripheral NS (the part of the nervous system that lies outside the brain and spinal cord) is comprised of two parts — the Somatic Nervous System which controls all conscious movements of the skeletal muscles, and the ANS which has unconscious control of all organs and the smooth muscles innervating them. It is not a stretch to say that our ANS IS our unconscious mind in our bodies.

The ANS’s primary function is to keep us alive at all costs—it manages risk and up- or down-regulates different body functions in response to our perceptions of safety or threat. Historically, this was thought of as a binary system similar to flipping a switch: Sympathetic (fight/flight) and Parasympathetic (rest/rebuild).

The ANS, together with the endocrine and immune systems regulate things like heart rate, breathing, digestion, hormone balance, and ultimately homeostasis, utilizing a highly sophisticated network of interconnections. In fact, every organ, system, and function of the body is coordinated by this communication between the brain and body via a close collaboration of neural (electrical) and endocrine (chemical) signals originating in the brain stem and diencephalon. Like a subroutine running in the background of our core operating system which controls absolutely everything (typically below conscious awareness).

Polyvagal Theory

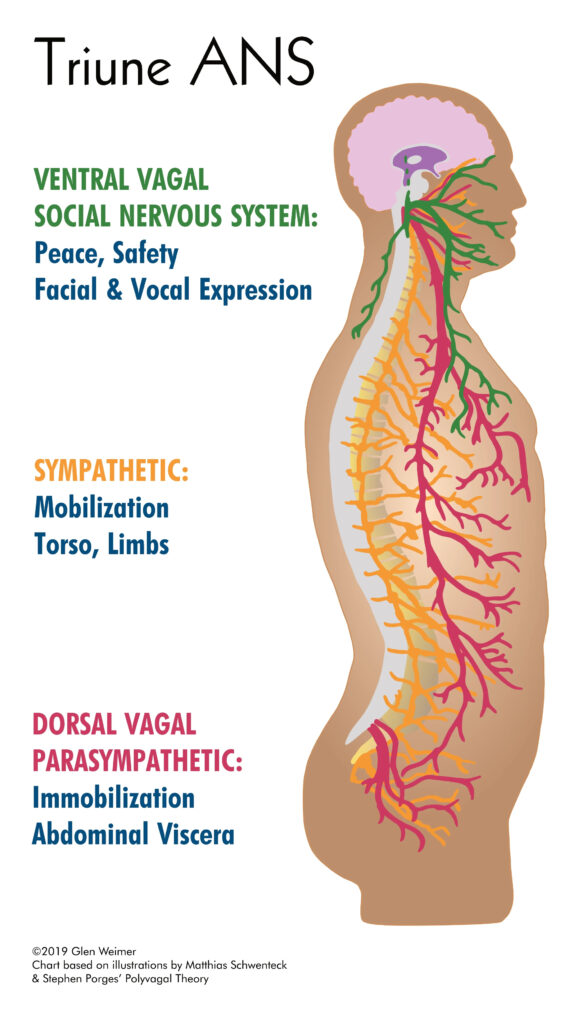

In 1994, Stephen W. Porges, Ph.D., developed the Polyvagal Theory (PVT), an entirely new model for understanding the functioning of the ANS. PVT was named for the multiple wandering branches of the vagal nerve complex, which creates a triune or 3-part ANS. This triune nervous system is sequential rather than reciprocal. Porges described how we draw upon these 3-branches based on our level of safety or threat. PVT links the 3-stage evolutionary development of our modern mammalian brain and autonomic nervous system to human social behaviors, our drive to bond, responses to threats, and adaptation to trauma/overwhelm. Porges recognized the traditional ANS model falls apart in understanding conditions like Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). There is a defensive/protective response that happens when individuals are pushed beyond fight or flight.

In 1994, Stephen W. Porges, Ph.D., developed the Polyvagal Theory (PVT), an entirely new model for understanding the functioning of the ANS. PVT was named for the multiple wandering branches of the vagal nerve complex, which creates a triune or 3-part ANS. This triune nervous system is sequential rather than reciprocal. Porges described how we draw upon these 3-branches based on our level of safety or threat. PVT links the 3-stage evolutionary development of our modern mammalian brain and autonomic nervous system to human social behaviors, our drive to bond, responses to threats, and adaptation to trauma/overwhelm. Porges recognized the traditional ANS model falls apart in understanding conditions like Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). There is a defensive/protective response that happens when individuals are pushed beyond fight or flight.

Neuroscientists estimate that 95 percent of brain activity is beyond our conscious awareness. It is as if we are going through life on autopilot. PVT provides the tools to understand the actual mechanism controlling this subconscious autopilot, how that is affected by stress and trauma, and empowers us to take control of our thoughts and actions, which ultimately changes both how we perceive life and how the world responds to us.

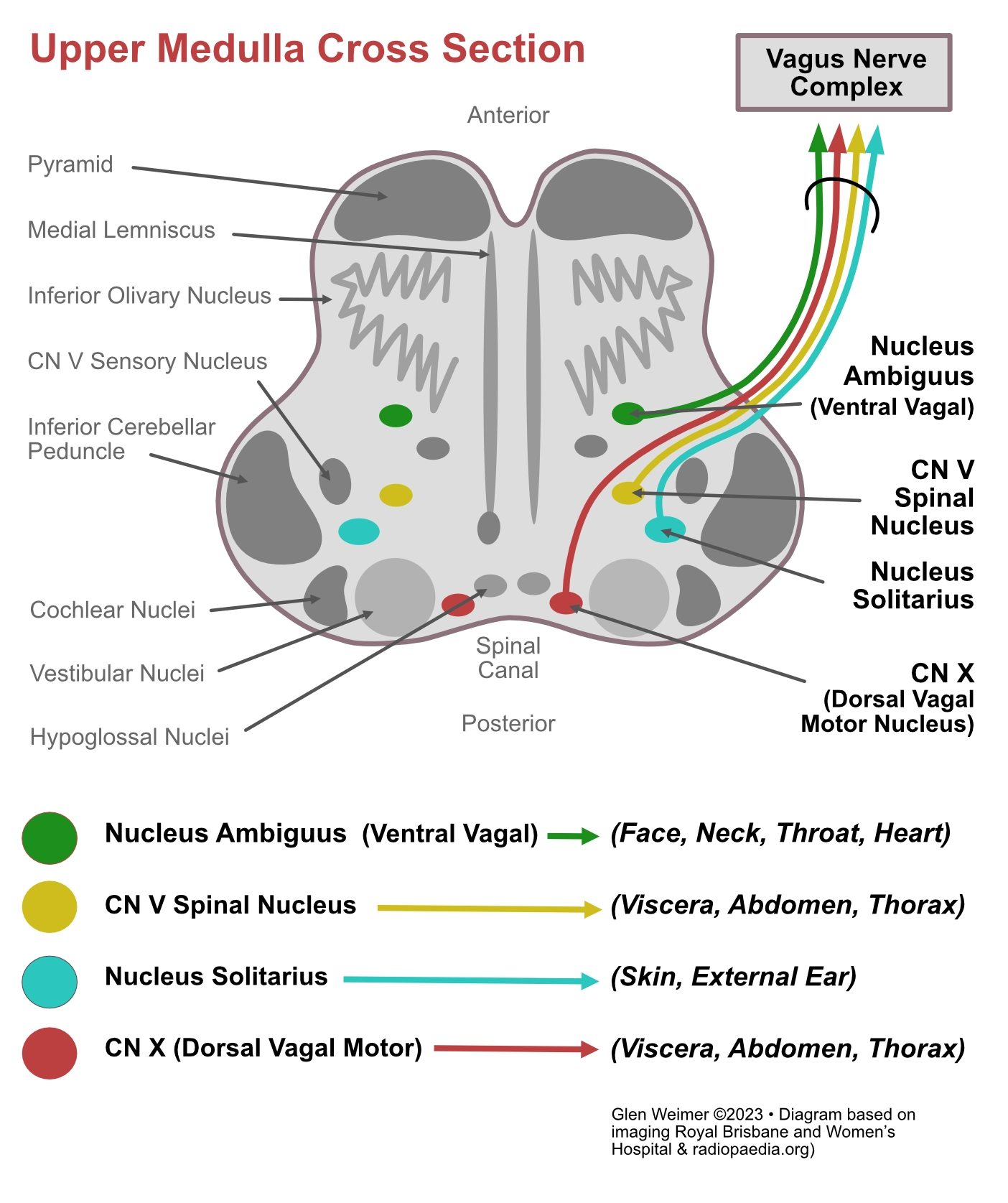

PVT looks at how the vagus or 10th cranial nerve (CN-X) interacts with four other cranial nerves to downregulate the sympathetic nervous system and return the system to homeostasis, known as the ‘vagal break’. He traces the pathways of these nerves, which have their roots in the nucleus ambiguus (NA) (efferent, motor nerves), the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) (afferent, sensory nerves), and the dorsal vagal motor neuron, which is a mixed sensory and motor pathway.

“The polyvagal theory requires a reconceptualization of the vagal system and the construct of vagal tone. The theory focuses on the cytoarchitecture of the medullary source nuclei of the cranial nerves. The theory takes an evolutionary approach and investigates, through embryology and phylogenetic comparisons, the common origins of the special visceral efferents and focuses on the shared medullary structures for the cell bodies of these fibers. The theory acknowledges that the vagal system is complex and should be organized not in terms of bundles of fibers leaving the medulla but rather in terms of the common source nuclei of several of these pathways. Functionally, the common source nuclei provide a center to coordinate and regulate the complex interactions among various end organs and are related to optimizing cardiopulmonary function.

Mammals, with their oxygen-hungry metabolic systems, require a special medullary center to coordinate cardiopulmonary functions with behaviors of ingestion (e.g., mastication, salivation, sucking, and swallowing), oral or esophageal expulsion (vomiting), vocalizations (e.g., cries and speech), emotions (e.g., facial expressions), and attention (e.g., rotation of the head). The NA plays this role and serves as the cells of origin of the smart vagus. The potent link between the NA and cardiopulmonary function observed in mammals is not observed in reptiles. In reptiles, which do not have nerves to regulate facial expression, the NA does not play a major role in visceromotor regulation.” Porges, (2010)

Stephen W. Porges, Ph.D

Dr. Porges, Ph.D., is a distinguished university scientist at Indiana University, where he directs the Trauma Research Center within the Kinsey Institute. He holds the position of Professor of Psychiatry at the University of North Carolina and Professor Emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago and the University of Maryland. He served as president of both the Society for Psychophysiological Research and the Federation of Associations in Behavioral & Brain Sciences and is a former recipient of a National Institute of Mental Health Research Scientist Development Award. He has published more than 250 peer-reviewed scientific papers across multiple disciplines.

3 Principles of Polyvagal Theory

Polyvagal Theory has three organizing principles.

- Neuroception

- 3-Tier Autonomic Nervous System

- Co-regulation

Neuroception

Neuroception is a term Dr. Porges coined to describe the mechanism that drives our ANS response. Different from perception, this occurs far below our conscious thoughts. It mobilizes all body functions necessary to meet that challenge. Author, Deb Dana says, “Before the brain understands and makes meaning of an experience, the autonomic nervous system, via the process of Neuroception, has assessed the situation and initiated a response.” (Dana, 2018)

Neuroception scans the environment, then mobilizes the Autonomic Nervous System to respond, which we ‘co-regulate’ through our relationships with others. Neuroception analyzes everything we see, smell, hear, and feel. It compares this current data to previous experiences of potential danger and engages a full-body multisystem response all before we are aware of any conscious impressions. When we meet a person, we often unknowingly scan their face, voice, and subtle gestures to determine how we should respond—are they friend or foe? We also compare the data, matching the criteria of prior traumatic incidents for colors, smells, sounds, anything that might indicate an unseen threat.

“We live a story that originates in our autonomic state, is sent through autonomic pathways from the body to the brain, and is then translated by the brain into the beliefs that guide our daily living. The mind narrates what the nervous system knows. Story follows state.” (Dana, 2018)

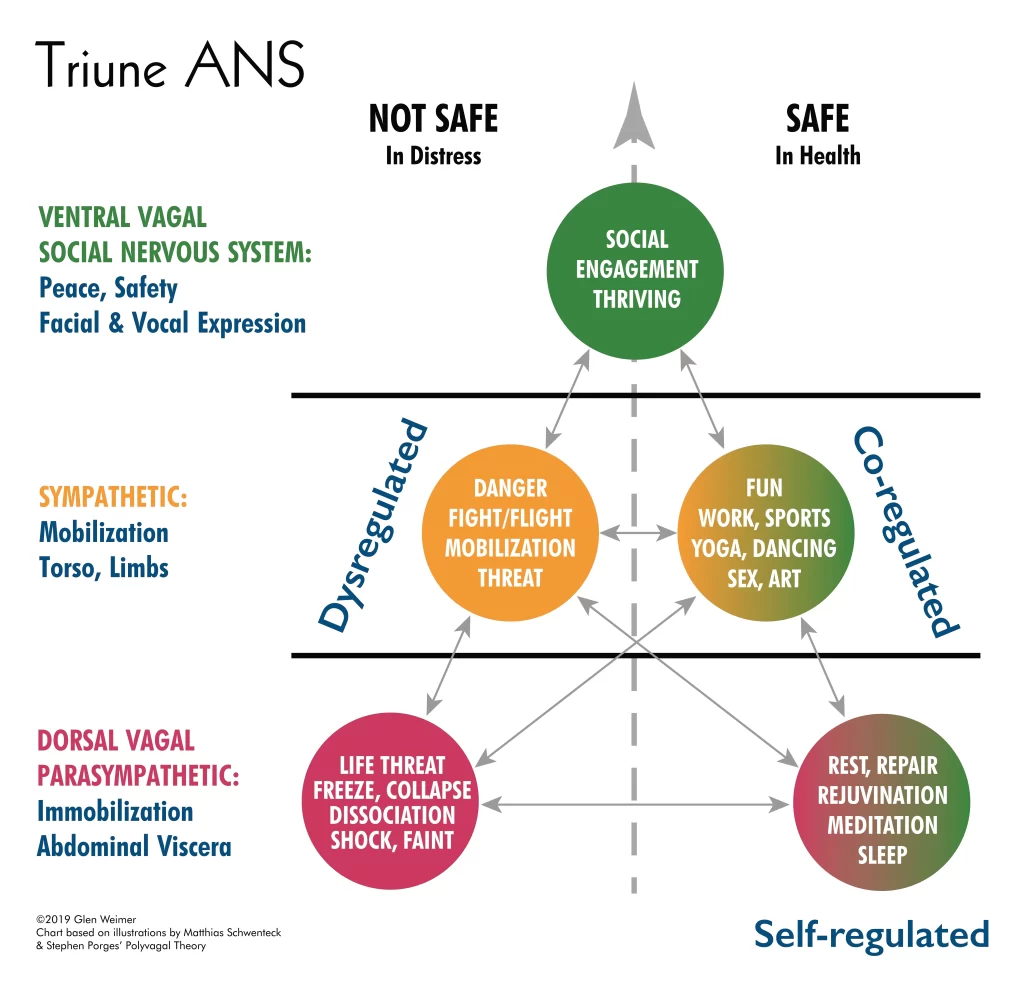

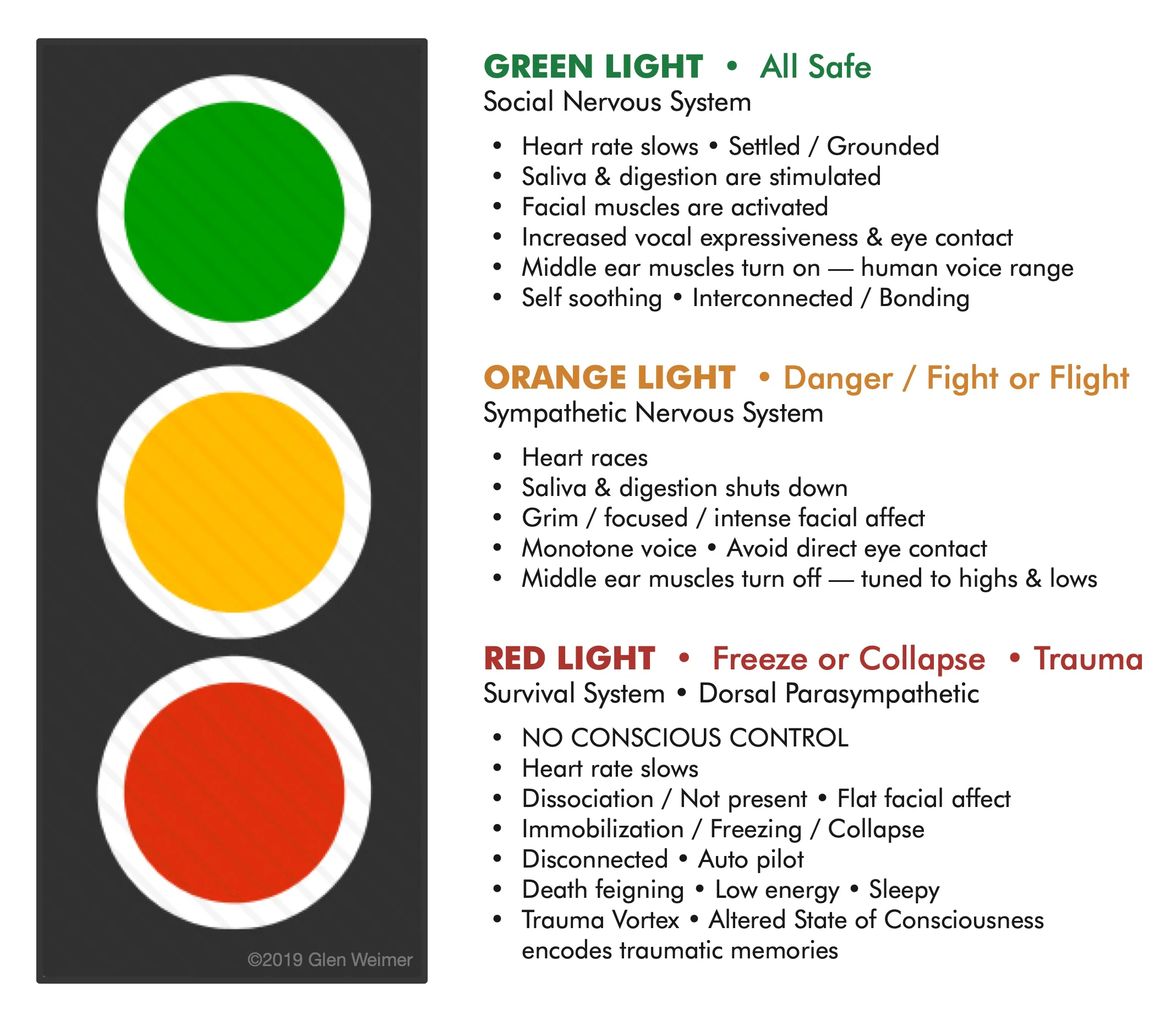

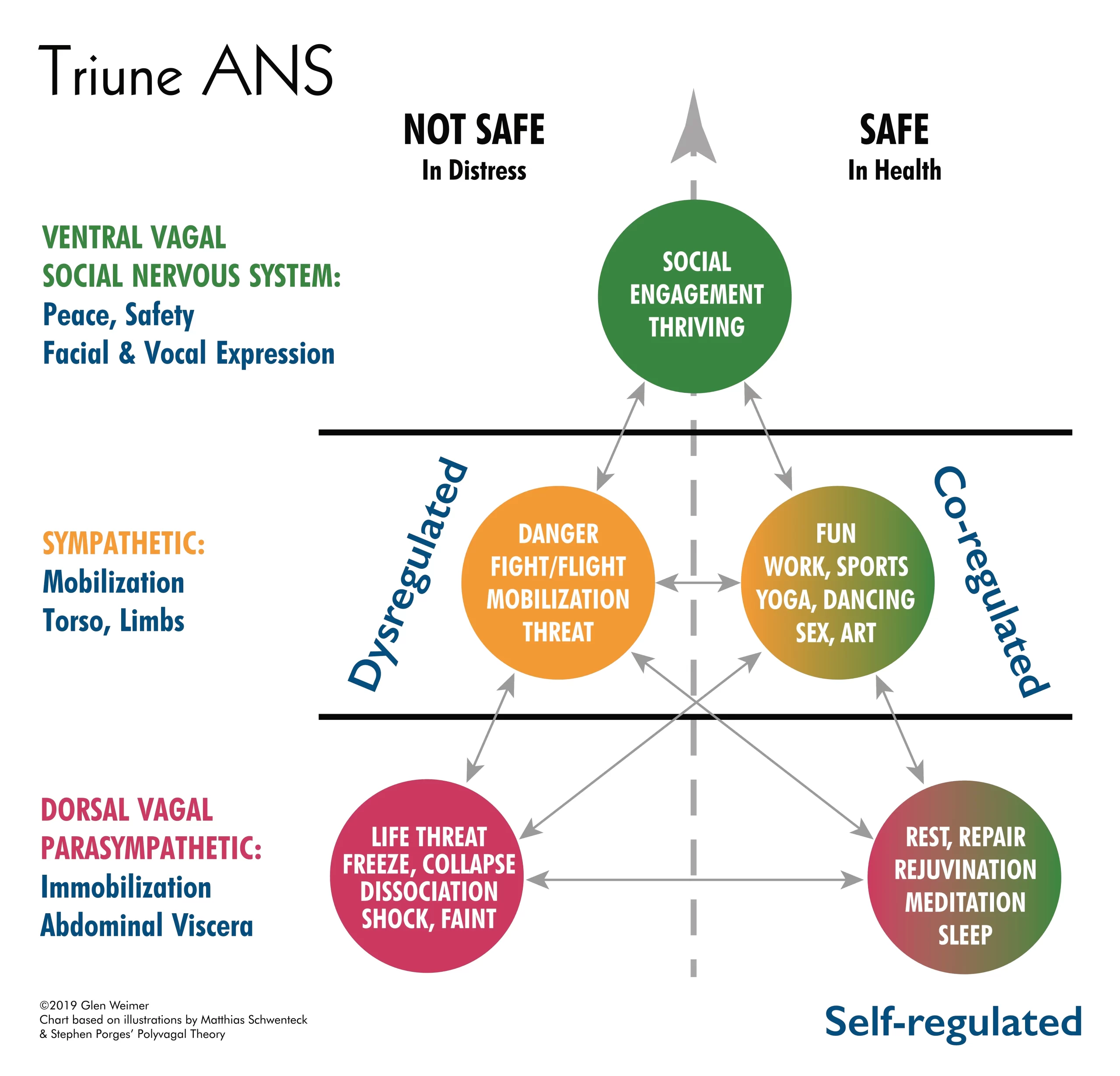

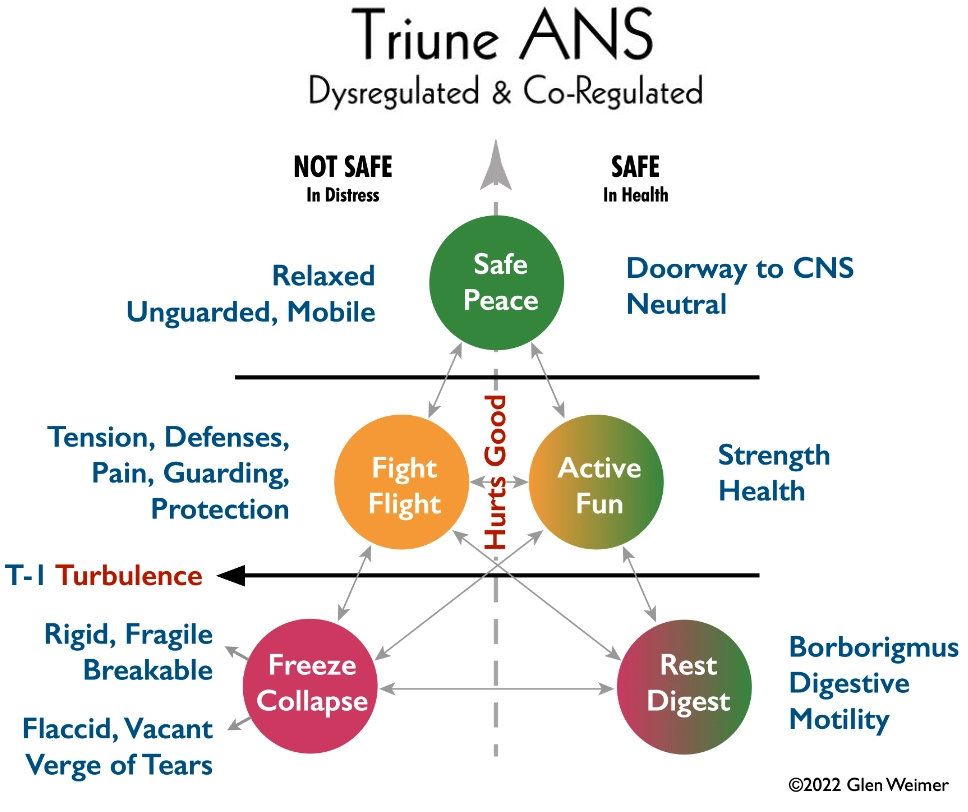

Polyvagal’s Triune ANS

Dr. Stephen Porges expressed his more nuanced ANS model as a hierarchy with three levels. These levels correspond to our evolutionary development as a species from reptile to early primate to human/modern mammal (reptilian brain, limbic brain, and neocortex). Three neural pathways form this evolutionarily ordered hierarchy that regulates behavioral and physiological adaptation to ‘Safe’, ‘Dangerous’, and ‘Life-threatening’ environments. Today this is often illustrated by the traffic light with GREEN representing our Ventral Vagal (VVC) (Safety/Social) Nervous System; ORANGE, our Sympathetic (SNS) (Fight/Flight); and RED, our (DVC) (Freeze/Collapse/Overwhelm) Dorsal Vagal Nervous System.

Porges likens it to playing cards; when we engage with others, we play our modern, best card first, VVC; engaging with eye contact, a smile, and a warm greeting. Neurologically, we are reaching out to connect. If not well received, we play our older, second card, SNS. When all else fails, we play our final card, DVC, which, in a state of overwhelm, we downregulate body functions, dissociate, and freeze or collapse.

Porges likens it to playing cards; when we engage with others, we play our modern, best card first, VVC; engaging with eye contact, a smile, and a warm greeting. Neurologically, we are reaching out to connect. If not well received, we play our older, second card, SNS. When all else fails, we play our final card, DVC, which, in a state of overwhelm, we downregulate body functions, dissociate, and freeze or collapse.

This three-card system is based on phylogeny, the study of the evolution of living organisms, specifically activating the brain in reverse evolutionary order. It recognizes a strategy that utilizes our most recent, advanced ‘Social Nervous System’ first in making contact. Secondly, we employ our SNS, which added ambulation, mobilization, and a wider possibility of options to ensure survival responses than our most primitive brain. Lastly, we access our oldest, most primitive brain, reflecting the survival strategies we have in common with our reptile ancestors. DVC “delivers nutrient-rich, oxygenated blood to the system, particularly the brain, and its components regulate heart, lungs and viscera. At a parasympathetic level, stress responses are primarily limited to adjusting the metabolic rate within a fairly narrow range, and “death feigning” survival tactics.” (Chitty, 2012)

Triune ANS Pathways

The Vagus or 10th cranial nerve (CN-X) establishes a direct line of communication, establishing a physiological link for the mind-body connection. It can be said to be the master switch for our Autonomic Nervous System (ANS). Dr. Porges described two distinct vagal pathways. Ventral Vagal (VVC – green) controls the muscles of expression: face, voice, hearing, heart lungs, and skin (generally front of the body above the diaphragm) primarily via cranial nerves V, VII, IX, X, XI, and X, all originating from the nucleus ambiguus (NA). The myelinated sensory fibers gather information from our visceral organs. If we are safe and healthy, these nerves facilitate social engagement and down-regulate sympathetic activation, our ‘Vagal Brake’. This myelinated ‘new’ or ‘smart’ vagal branch innervates and controls the upper third of the esophagus and most of the pharyngeal muscles, and it regulates the heart and bronchi.

The Vagus or 10th cranial nerve (CN-X) establishes a direct line of communication, establishing a physiological link for the mind-body connection. It can be said to be the master switch for our Autonomic Nervous System (ANS). Dr. Porges described two distinct vagal pathways. Ventral Vagal (VVC – green) controls the muscles of expression: face, voice, hearing, heart lungs, and skin (generally front of the body above the diaphragm) primarily via cranial nerves V, VII, IX, X, XI, and X, all originating from the nucleus ambiguus (NA). The myelinated sensory fibers gather information from our visceral organs. If we are safe and healthy, these nerves facilitate social engagement and down-regulate sympathetic activation, our ‘Vagal Brake’. This myelinated ‘new’ or ‘smart’ vagal branch innervates and controls the upper third of the esophagus and most of the pharyngeal muscles, and it regulates the heart and bronchi.

The unmyelinated Dorsal Vagal (DVC – red) branch controls the brain stem, digestion, reproduction, and the immobilization of the limbs (generally below the diaphragm, governing core survival functions). This ‘older’ CN-X branch innervates the lower two-thirds of the esophagus; it regulates stomach function, digestive glands and organs such as the liver and gall bladder, and movement of food through the intestines (except the descending colon).

The third pathway is the Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS – orange), which comes off of a trunk or chain of nerves running alongside the spine at the level of the chest and low back (controlling mobilization of the torso, arms, and legs to fight and/or flee). Each system upregulates certain body functions and downregulates opposing ones.

7 Functional ANS States (+2)

7 Functional ANS States (+2)

Most often, PVT is described using a Triune ANS model. This is only partly true. This simply describes the three primary pathways of the theory, often focusing mostly in distress/protection. Functionally, PVT actually has five states: 1) VVC, 2) dysregulated SNS, 3) co-regulated SNS, 4) dysregulated DVC, and 5) co-regulated DVC. Additionally, the two dysregulated states can each be subdivided into two distinct states (SNS = Fight and Flight, DVC = Freeze and Collapse). Conversely, the two co-regulated states can be understood as healthy hybrid modes, when SNS activation occurs within a context of safety (VVC), it enables us to play and have fun rather than move into fight or flight; when the two branches of vagal pathways (DVC and VVC) are co-regulated the body moves into a state of rest/rebuild/repair where sympathetic activation is downregulated and blood flow and physiological activity are directed away from the periphery, toward the GI tract. This allows us to settle our nervous system and bring our attention inward in safety.

I would add to the PVT model an eighth and ninth, which are Trauma states, ’T-1’ which encodes and stores traumatic events in the nervous system, and ’T’ which perpetuates post-traumatic maladaptations by creating the two dysregulated DVC overwhelm states of freeze and collapse.

We will begin with an overview of all these states, then an explanation of how I have used them clinically over the last 30 years. Finally, we will present a hypothetical model to apply these in bodywork therapy.

GREEN LIGHT • Social (VVC)

Our most modern response, and the one which distinguishes humans and modern mammals, is our ability, at least in theory, to be in proximity to one another without attacking or responding to everything as a threat. This is the Ventral Vagal pathway of our ‘Social’ Nervous System. This state begins to develop with pre- and perinatal mother-child bonding, attachment, skin-to-skin contact, nursing, care, and our earliest social interactions with our world. In PVT it is said that safety allows for proximity, proximity allows for contact, contact for bonding, and bonding enables us to thrive. Everything comes back to safety.

Our most modern response, and the one which distinguishes humans and modern mammals, is our ability, at least in theory, to be in proximity to one another without attacking or responding to everything as a threat. This is the Ventral Vagal pathway of our ‘Social’ Nervous System. This state begins to develop with pre- and perinatal mother-child bonding, attachment, skin-to-skin contact, nursing, care, and our earliest social interactions with our world. In PVT it is said that safety allows for proximity, proximity allows for contact, contact for bonding, and bonding enables us to thrive. Everything comes back to safety.

In Ventral Vagal our brains produce oxytocin, sometimes known as the cuddle or love hormone, which engages brain areas involved in processing our socializing, bonding, pleasure, and reward systems. The ears are tuned to the range of the human voice and cues to affection and inclusion.

When VVC and DVC are coregulated by safety, our energy and blood flow are centered in our core for tissue repair and recovery, and our breathing and heart rate are slow and measured. Our digestive system is engaged in breakdown, assimilation, and elimination. And we suppress adrenaline and stress hormones and engage higher cortical brain activity, such as cognition, attention, and memory.

ORANGE LIGHT • Danger (SNS)

If we feel threatened in any way, our Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) engages the more primitive part of our mammalian brain: the Fight-or-Flight response; activating the body to fight or run away from the perceived threat. Designed by evolution to mobilize us into immediate action, it downregulates all non-essential body functions such as the digestive and reproductive systems. And diverts the blood flow out to the big muscle groups in the neck and shoulders to fight, and to the low back, butt, and legs to take flight.

This is meant to be an instant response to an imminent threat. Unfortunately, we are using the same response that served us well in the jungle to meet the minor challenges of our modern world. Additionally, we often don’t feel like we can act in these settings, so the SNS is continuously engaged in a frustrated Fight-or-Flight pattern. The body holds a standing tension in the upper body when social, moral, and ethical constraints keep us from striking out because it’s our boss, a client, or family member. Alternatively, we hold this frustrated Fight in our jaw, face, base of the skull, and neck when we ‘bite our tongue’ and hold back expressing what we think and feel. We hold on to the Flight response in our low back, psoas, butt, and leg tension when we can’t run away from our problems or leave a boring/uncomfortable conversation.

When SNS is co-regulated with VVC, this activation response looks completely different. We begin to train newborns in this skill immediately after birth with the game of peekaboo. This simple game is ubiquitous around the planet, and infants can’t get enough of it. The key factor for co-regulation is that SNS mobilization occurs within a context of safety, which gets the child to associate SNS activation with fun. As the child matures, peekaboo gives way to tag, dodgeball, red rover, and football. As the games become more intense, the child learns to engage life as a challenge/adventure.

RED LIGHT • Freeze-Collapse (DVC)

If our nervous system determines that there are no good options to avoid the threat, we engage the Dorsal Vagal branch, our Parasympathetic Nervous System (DVC), or freeze-collapse response. This is the most primitive part of our reptilian brain. In this state, we believe death is imminent and therefore numb and dissociate from our body as we surrender to complete overwhelm.

For children who did not learn SNS co-regulation, either because their home or community was not a safe place, DVC freeze-collapse became the learned response and the default response to stress. Whenever overstimulated, stressed, or anxious, rather than mobilizing, these individuals collapse. This can often lead to self-medicating, dissociating, life-avoidance/escape (fantasy, TV, books) or sleeping to avoid the awful feelings, situations, or memories. This can lead to feeling barely alive.

This state makes the process of addiction recovery very difficult. As soon as a person returns to a ‘normal’ state of consciousness or starts running more energy through their bodies to reengage with life, they begin to feel that nervous system activation and the return of those intense, unpleasant feelings, so they fall back into addiction/avoidance behavior.

Co-regulation

Polyvagal Theory identifies Co-regulation as a biological imperative: a need that must be met to sustain life. We regulate our ANS together with others through our relationships. Others can agitate and activate us, but conversely, through co-regulating, we can feel safe enough to move into connection and create trusting relationships that enable us to thrive physiologically and in our lives. Practiced co-regulation gradually enables us to self-regulate.

Polyvagal Theory identifies Co-regulation as a biological imperative: a need that must be met to sustain life. We regulate our ANS together with others through our relationships. Others can agitate and activate us, but conversely, through co-regulating, we can feel safe enough to move into connection and create trusting relationships that enable us to thrive physiologically and in our lives. Practiced co-regulation gradually enables us to self-regulate.

All three ANS states are self-reinforcing, in that we perceive our world as being identical to the state we are in. When we feel safe, we experience a nurturing and supportive world; when threatened, we see danger everywhere. Healthy, loving relationships enable us to get close to others and form bonds of friendship and love. Without this, our perception of a dangerous world forces us to keep everyone and everything at a safe distance. Likewise, physiologically, our bodies are either in growth, nourishment, thriving mode, OR in protection mode where nutrients are ‘blocked’ from entering the tissues and the BMS functions as isolated, uncoordinated parts.

It is not an exaggeration to say that without love we wither and die. It’s precisely this that has been documented in various scientific studies of newborns deprived of physical contact and bonding shortly after birth (Chapin, 1915; Prescot, 1971). Porges observed that our webwork of interconnections empowers us to meet life’s challenges. The co-regulation of VVC (safety-mode) with both SNS and DVC is at the heart of the PVT model in healthy individuals.

PVT and the Evolution of Trauma Therapy

Since its initial proposal in 1994, PVT has become widely adopted and utilized worldwide within the fields of psychology, psychiatry, and trauma therapy, especially with body-centered or somatic approaches. Numerous books have been written on PVT and countless peer-reviewed research papers from prominent universities around the world have applied it clinically to everything from PTSD to COVID-19, childhood development disorders to aberrant social behaviors. Despite this, PVT has had limited inclusion in touch therapies other than Energy- or Consciousness-based (biofield) bodywork therapies like Polarity and CranioSacral therapy, which often combine traditional Energy-based (biofield) touch with verbal body-centered trauma work.

Body-Centered or Somatic Psychotherapy describes therapeutic approaches that integrate a client’s physical body into the therapy process. These processes recognize the interrelationship between the human body and the psychological well-being of a person. Somatic therapies enable clients to heal traumatic experiences and chronic stress by focusing on the physical body and body sensations. Through the use of movement and guided exercises, clients are taught to recognize how stress and trauma are stored in the body, how the mind and body are connected, and how to use specific exercises to release the emotional pain that is stored within the body.

PVT & Trauma in Bodywork

Massage and manual manipulations, in their multiple forms, are often ‘outside-in’ therapies using various hands-on techniques to convey an external mechanical directive in order to elicit a therapeutic response from the client’s body — ‘stop doing this, start doing that’. In outside-in therapies, the therapist imposes their will, intention, and directive for the tissue field to change in accordance with a perception and criteria of ‘correct’ alignment and function. This is an active mechanistic approach focused on addressing dysfunctions, impairments, and pathologies in the anatomy and physiology of the musculoskeletal-fascial system. Additionally, most bodywork approaches focus solely on frustrated Sympathic holding, oblivious to the greater issue of Dorsal Vagal freeze/collapse or how to address it.

“Humans are not assembled out of parts like a car or a computer. ‘Body as machine’ is a useful metaphor, but like any poetic trope, it does not tell the whole story. In our modern perception of human movement anatomy, however, we are in danger of making this metaphor into the be-all and end-all. In actual fact, our bodies are conceived as a whole, and grow, live, and die as a whole – but our mind is a knife.” (Meyers, 2023)

By contrast, Polarity Therapy and other Energy-based (biofield) modalities are inside-out approaches, engaging the organizing Consciousness that creates and sustains body physiology to invite changes from within the client. The inside-out approach is client-driven/client-centric, which begins and ends in stillness and the subtle dynamics of the client-therapist relationship. Here, the therapist recognizes that the client’s own system knows exactly what it needs in order to self-correct. It is the bodywork equivalent of reflective listening utilized by psychologists, “I heard you saying your right shoulder hurts”. Only in this instance, through touch, the therapist reflects back to the BM System, ‘This is what I see you doing, is this what you want to be doing? Is there a way you can be more at ease? How can I help you get there?’

These systems approach the body from two contrasting worldviews, one mechanistic, the other vitalistic. When working from a mechanistic paradigm, with the body no more than a biological machine, it is easy to identify a problem, then take prescribed steps 1, 2, and 3 to fix it — that’s the outside-in approach. The vitalistic worldview, on the other hand, acknowledges an X-factor, beyond what can be seen and measured, that must be factored into our understanding of life. This involves a more nuanced and creative path that consciousness (Lifeforce) takes in both bringing living systems out of balance and returning to homeostasis. Utilizing an understanding of its governing principles, each vitalistic practitioner engages in the therapeutic relationship as one of consciousness-to-consciousness, Life-force to Life-force; navigating the internal fears and traumas which are at the heart of what keeps all Energy from flowing freely, and form from expressing health.

Even when utilizing what looks to be similar techniques, the therapist’s perception and understanding of what they are doing provides the client with distinctly different experiences and outcomes. Most people have never experienced anything other than typical massage, chiropractic, or other outside-in therapies so they have no point of reference for what I’m trying to explain.

Even when utilizing what looks to be similar techniques, the therapist’s perception and understanding of what they are doing provides the client with distinctly different experiences and outcomes. Most people have never experienced anything other than typical massage, chiropractic, or other outside-in therapies so they have no point of reference for what I’m trying to explain.

It is vitally important to note that there are bad, mediocre, and exceptional therapists in ALL fields. Many bodyworkers in ‘traditional’ modalities, whether by training or intuition, incorporate aspects of this nuanced inside-out approach. This is a description of the systems/paradigms, not individual practitioners.

“In my own practice, I preferred biomechanical craniosacral therapy, which reminded me of my work with Rolfing… I practiced various forms of body-oriented therapies for more than thirty years, but I eventually realized that I was using the wrong map. When I learned about Stephen Porges’s Polyvagal Theory, his ideas expanded my understanding of how the autonomic nervous system functions, and immediately I had a better map” (Rosenberg, 2017)

PVT’s Incorporation into Bodywork Today

Currently, to my knowledge, Polyvagal Theory is only being incorporated into a few biofield (Energy- or Consciousness-based) therapies such as Polarity (PT) and CranioSacral Therapy (CST). It was incorporated into these fields because of their emphasis on 1) energy fields and their subtle tissue, fluid, and energetic movement, 2) settling the nervous system, 3) stillness as the root out of which movement emerges and returns, 4) subtle psychoemotonal energetic aspects of the client-therapist relationship, 5) the interconnectedness of the quantum field phenomena in healing, and 5) the body-mind connection.

Additionally, both PT and the biodynamic branch of CST incorporate verbal body-centered counseling in conjunction with hands-on bodywork. They each have traditional (pre-existing) bodywork techniques for addressing the nervous system. Much of CST focuses on assisting the client’s system to navigate internal turbulence and orient to stillness. PT founder, Dr. Randolph Stone, was a cranial osteopath and developed unique ANS balancing techniques with specific gentle contacts for the Sympathetic and Parasympathetic pathways.

Other manual therapy fields that work with the myofascial system, such as direct, indirect, functional indirect, and biodynamic indirect approaches, (like Muscle Energy Technique, Myofascial Release, Jones’ Strain Counerstrain, Neurotissue Tension Technique, and Functional Technique), work holistically since they are engaging the BMS’s ‘superhighway’, the myofascial system. Although, to my knowledge, they do not work with PVT specifically, in their own way they each work with some aspect of the body-mind system, trauma, ANS-endocrine-immune system, and limbic-hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis.

My Application of PVT in Clinical Practice

Ease – Ventral Vagal Safety

Ventral Vagal Complex (VVC) – When the body is in Ventral Vagal or safety mode we are able to truly drop our defenses. Without this, we are perpetually on guard, in some level of self-protection, ‘bracing for impact’; either in Sympathetic (Fight-or-Flight) readiness like a bowstring pulled and poised to be loosed at any moment, or Dorsal Vagal overwhelm, with tissues frozen-rigid or flaccid-collapsed.

What VVC looks like in the body is EASE! It’s a relaxation of all the muscles engaged in defense, particularly the skeletal muscles of the jaw, neck, shoulders, and arms. The fist can unclench and the hands can relax. The low back, butt, and legs can let go, and we have the felt-sense of grounding, dropping into the soles of our feet, and planting ourselves within our bodies in the present moment. Physiologically, the heart rate slows and breathing becomes measured and steady. In fact, VVC is the only Autonomic state where the breath can move effortlessly in and out of the lungs in a slow, steady rhythm. The heart also drops into an easy, measured rhythm, employing increased heart-rate variability (HRV). The blood flow returns to the lower digestive tract, which secretes digestive juices and upregulates peristaltic motility.

In Ventral Vagal, stress hormone production of adrenaline, norepinephrine, and cortisol decreases and is replaced by the production of ‘feel-good’ hormones like dopamine, oxytocin, serotonin, and endorphins.

VVC is our Safety mode that both enables connection with our outer world and also disengagement to move deeply into our inner reality. Our ability to co-regulate our ANS radically affects the expression of the other branches, the Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) and Dorsal Vagal Complex (DVC).

When I’m working with a client, the first thing I do is breathe and relax. By settling my own nervous system and my body physiology, and relaxing my muscles, I begin to entrain/invite my client’s system to do the same. My ANS is informing their ANS ‘I am a safe person and won’t hurt you’.

As I engage their tissue field, I think of T’ai Chi push-hands. If the client is in Ventral Vagal, when I mobilize or engage a part of the body, it feels like a fluid dance where I’m never quite sure who’s leading and who’s following. My hand and the client’s hip and knee, for example, glide effortlessly through space. That demonstrates to me the client’s level of ease in their interaction with the outside world. What quickly becomes apparent is the level to which the client needs to brace themselves and control what’s going on. The same is true whether I am making contact with a joint or if I have my hands in the middle of a muscle belly, bone, or organ. The myofascial tissue field should be able to glide effortlessly in all directions without restrictions.

As I engage their tissue field, I think of T’ai Chi push-hands. If the client is in Ventral Vagal, when I mobilize or engage a part of the body, it feels like a fluid dance where I’m never quite sure who’s leading and who’s following. My hand and the client’s hip and knee, for example, glide effortlessly through space. That demonstrates to me the client’s level of ease in their interaction with the outside world. What quickly becomes apparent is the level to which the client needs to brace themselves and control what’s going on. The same is true whether I am making contact with a joint or if I have my hands in the middle of a muscle belly, bone, or organ. The myofascial tissue field should be able to glide effortlessly in all directions without restrictions.

Everything other than this fluid T’ai Chi-like motion is some aspect of protective armoring. If there’s resistance, jerkiness, barriers to movement, or if they are ‘helping me,’ this shows me their system’s strategies for protection/defense. My question for myself is, how can I help my client navigate their BMS back to ease? Ease, peace, safety, and relaxation are all synonymous in this context.

When we think about threats from the outside world, we imagine being punched, hit, run over, and the like. More often, we are concerned for our mental and emotional safety—how people perceive us, what they think or say to others about us, how our loved ones may be affected, or how situations will impact us financially. In essence, “How can this moment adversely impact my future?”

Activation – Sympathetic Protection

Dysregulated SNS, (without a sense of safety), a frustrated Fight-or-Flight state, creates a contraction in the tissue field as the muscles tense and ready themselves to spring into action at a moment’s notice. This should be a brief state of threat followed by an immediate explosion of activity. When the action is delayed for hours, days, or decades, the tissue field holds a pattern where all the structures are in tight proximity to one another; muscles, tendons, ligaments, and joints are in a contracted relationship, and nerves get pinched by either these tense soft tissues or a displaced bony alignment. We refer to this as a state of chronic stress or distress. This change in the shape of the tissue and energy fields affects the proper functioning of the organs, and the protective SNS or DVC state signals systemic changes to all organ physiology to match these protective Autonomic states.

The breath, along with that tissue field, is held in a perpetual bracing inhale, waiting to be used in sudden explosive action. In fact, the contracted muscles cannot release until the client exhales and lets go of that standing tension. Bodyworkers and yoga teachers alike utilize this exhale to facilitate relaxation.

The challenge is that Autonomic states are self-reinforcing; meaning that if I feel safe, I see smiling, happy people everywhere, but if I don’t feel safe, all I can see is danger, threats, and angry, unhappy people. Consciousness associates the pain and unpleasantness of this state with thoughts and emotions (story and felt-sense feelings) that match — ‘I’m in pain’, ‘I’m pissed off’, ‘it’s a dangerous world’, and ‘life sucks because of ___’ (fill in the blank.) As Deb Dana says, “Story follows state!”

Physiologically, the initial signals of threat cause an instantaneous release of stress hormones, like adrenaline to course through the body, putting the system on high-alert, so it can immediately respond if/when needed. The frustrated SNS state that isn’t discharged through action also utilizes other hormone activators like cortisol to deal with the sustained stress. Cortisol maintains that ‘ready’ state. These stress hormones constrict blood vessels; elevate heart rate; upregulate the body’s metabolism to burn fats, carbohydrates, and protein to fuel necessary actions; increase glucose (sugar) levels in the blood; maintain wakefulness; and suppress tissue repair. It’s easy to connect the dots between conditions relating to blood pressure, blood sugar, and sleep disorders, with chronic Sympathetic dysregulation.

Downregulating that state requires perceiving that the threat has, in fact, passed; you are now safe and don’t need to remain on guard to prevent something bad from happening. The question is, how long will you believe that you are still safe before you need to go back on ‘guard duty’ for the potential reemergence of that same issue or a new threat?

When clients on my bodywork table experience releasing frustrated Sympathetic hypervigilance and return to a balanced VVC state, their whole nervous system downregulates. They describe it as getting really heavy, becoming part of the table, feeling drowsy, or being in a dreamlike state. I can perceive that as their mind and body go ‘off-duty’, they no longer need to remain vigilant. Muscle tension patterns throughout the body can let go from the inside.

When clients on my bodywork table experience releasing frustrated Sympathetic hypervigilance and return to a balanced VVC state, their whole nervous system downregulates. They describe it as getting really heavy, becoming part of the table, feeling drowsy, or being in a dreamlike state. I can perceive that as their mind and body go ‘off-duty’, they no longer need to remain vigilant. Muscle tension patterns throughout the body can let go from the inside.

SNS is a state of activation or mobilization. The heart rate increases, pumping more blood to peripheral tissues to fight or run. When the body is in a dysregulated state, meaning that it perceives a threat from which it has to protect itself, it prepares for action. As previously stated, this causes pain, tightness, bracing, and constriction/restriction, as the tissue field coils inward in contraction.

I often engage this therapeutically by meeting that tension with a matching force. I may either press into that area, or, conversely, I may hold ‘the holding’ for the client by tensing my own body while making contact with that tense area. Unlike outside-in therapeutic approaches, it is never my goal to force the tissue field to let go; in fact, I have NO GOAL other than to be present with the system and see what it wants. I work from an understanding that I am engaging with body-consciousness, which is truly what’s doing the holding. Therefore, all I need to do is help the system recognize its defensive patterns, and that it has options, one of which is to release that standing tension. When the decision to let go or change comes from within, its effects are long-lasting.

A deep bodywork contact at the area of contracted tissues drives consciousness to that specific area. In Polarity Therapy, this is called ‘Tamasic’ touch. Most people have only ever experienced techniques that prod, stroke, or manipulate the tissues, demanding change from the outside-in. In those cases, the BMS can only ever demonstrate its protective ANS responses to an external threat. Body-consciousness identifies it as ‘me’ versus ‘other’ and enlists whatever defense strategies it can.

The REAL therapeutic work happens when we assist the client in disengaging that perception of outside threat rather than reinforcing it. If I engage with a deep contact into the tissue field, once the client’s body-consciousness shows up, we’re ready to begin ‘walking back’ away from the perception of threat. At that point, I can increasingly soften my contact. The internal message that the client receives is ‘Oh, there is no threat in this movement. I’m safe. I can let my guard down.’ No matter how deep the bodywork contact is, the client’s true letting-go only happens when the therapist disengages or softens the contact. Otherwise, from my perspective, their system has likely engaged DVC and succumbed to overwhelming force, ‘saying uncle’ and submitting versus relaxing.

This softening touch can even progress to still or gentle on- or off-body contacts where it looks like the therapist isn’t doing anything. That’s when the nervous system can downregulate, shifting from its protective ANS states of SNS and DVC to its safety state of VVC; ultimately, able to rest and reorganize in the Central Nervous System (CNS). This is the mechanism utilized by Energy-based systems, which also enables the nervous system to integrate the work being done.

Co-Regulated SNS

When SNS is co-regulated, the system experiences activation within a safe container. It sees this stimulus as fun, as an adventure, a challenge to pit itself against its own limits. This is a VERY different internal state, perception, and felt-sense. Therapeutically, the tissue field feels completely different than it does in the dysregulated SNS state. Here, the client is aware of feeling strong, experiencing an inner felt-sense of the vitality and strength of their muscles and tissues. As a therapist, I experience something similar when I engage with this energy pattern, the tissue feels strong, juicy, vibrant, and alive.

When SNS is co-regulated, the system experiences activation within a safe container. It sees this stimulus as fun, as an adventure, a challenge to pit itself against its own limits. This is a VERY different internal state, perception, and felt-sense. Therapeutically, the tissue field feels completely different than it does in the dysregulated SNS state. Here, the client is aware of feeling strong, experiencing an inner felt-sense of the vitality and strength of their muscles and tissues. As a therapist, I experience something similar when I engage with this energy pattern, the tissue feels strong, juicy, vibrant, and alive.

Additionally, there is a halfway point between co- and dysregulated SNS, which is universally experienced as the ‘Hurts-Good’ state. When we engage with this kind of tissue field, clients will often say, “Oh my God, that hurts, but don’t stop.” They are aware of both the contraction with nerve impingement and pain (dysregulation), and simultaneously their own underlying strength and capacity to meet the challenge, let go of the perception of threat, and teach themselves to co-regulate their system. This is a HUGE opportunity for clients to retrain their unconscious automatic, autonomic system’s response to threat, to shift from associating activation with threat, to fun or challenging adventure.

Having said all of that, it is impractical and not ideal to have a completely relaxed system at all times. There should be a certain level of Sympathetic protective engagement. If I engage with the body and it is already flaccid, I am on the alert for the possibility of DVC collapse.

“Sometimes it’s a fleeting event that sparks a moment of protection, and sometimes we find ourselves in situations with the ongoing potential to take us out of connection into protection. None of us can stay permanently engaged with the world and the people around us from our patterns of connection [VVC]. It is an unreasonable, and unattainable expectation of ourselves and others. In fact, it is our ability to recognize when we move into a place of protection and find our way back into connection that is the hallmark of resilience [and health]…

Some days finding my way out of protection feels beyond my reach, and other days I’m able to easily find my way back to my anchor in connection.” (Dana, 2022)

In my practice, when I work with clients’ dysregulated Sympathetic states, we disengage the pattern somatically and also reinforce this with body-centered dialogue to disentangle the underlying perceptions and triggers.

Athletes who are used to pitting themselves against external challenges have a far greater capacity to co-regulate their SNS than the rest of us. They often seek out, enjoy, and have an easier time with deep tissue bodywork because they’ve trained their systems to self- and co-regulate fluidly in intense situations. It is, in fact, their ability to access the ‘hurts good’ state within a higher pain threshold that enables them to navigate to an optimal co-regulation in ways beyond the capacity of non-athletes.

For others, deep massage can cause what the old osteopathic doctors referred to as secondary lesions or adhesion patterns in the myofascial connective tissue. Here, the system sets up an initial holding pattern or inertial fulcrum from an injury/trauma, which distorts and constricts the tissue and fluid fields. And then a secondary holding pattern of defense, or more commonly freeze or collapse in response to overwhelming therapeutic force. These clients may experience short-lived relief followed by adverse effects of pain shortly after a session which can last for several days as the BMS figures out how to accommodate a new secondary distortion pattern.

T & T-1 (Trauma & Trauma Minus One)

As the BMS becomes pushed to and beyond its limits, it employs a brilliant survival strategy to ensure its continued existence. T-1 and T are at the heart of the creation of the ‘Trauma Vortex’. Neurologically, the ANS is suddenly shifting gears between high adrenaline activation (SNS) and complete DVC shutdown. Picture an automobile going from 120-MPH to full-stop in a fraction of a heartbeat.

“David Grove, a psychologist from New Zealand, who researched the dynamics of trauma encoding, referred to this as “T minus one” (T-1), indicating one millisecond prior to the trauma itself. I shall employ his terminology, as it is accurate and descriptive when discussing the nature of trauma. “T-1” is a most important concept. Most of us avoid accessing memories for fear of fully re-experiencing the original pain. We now understand that: 1) the inherent design and function of our nervous system helps us to avoid retraumatization, and 2) it is not necessary to relive the entire emotional experience in order to heal. We do not encode the whole experience; we encode only the peak (T-1) moments. Therefore, we do not have to relive the entire experience to obtain resolution. This phenomenon was noted when studying Vietnam veterans and discovering that their flashbacks were not their worst moment or “T” itself, but were an incredibly vivid experience of T-1. At T-1, the mind and nervous system, through the functioning of the limbic-hypothalamic system of the brain, consolidate all the incoming data and encode this information in holographic form—as metaphor. This metaphor (as referenced earlier) is simply the fragment of the larger holographic scene.” (Baum, 1997)

T-1, the millisecond before Trauma encodes in the BM System, is indicated by an upwelling of overpowering emotions and/or pain that overwhelms the system. For that fraction of a moment, chaotic turbulence surges through the nervous system as the BMS scrambles for some unseen option, a physiological or defense mechanism to change the situation. This is often accompanied by uncontrollable trembling, twitching, numbness, dissociation, waves of full-body convulsions, sobbing, immobility, or paralysis.

Once neuroception recognizes that no action will avoid a negative outcome or unbearable pain, its only recourse is to enter T, a self-induced trance state which pauses time and encodes a multisensory holographic fragment of the event to process at a later moment (if there is one). T is a containment process facilitated by the limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (LHPA Axis) in the brain, which regulates the functioning of the ANS, the endocrine, and immune systems. The BMS often involves a protective or memory-repressive function, including full or partial amnesia of the event(s). It abruptly puts the brakes on sympathetic activation and initiates the engagement of the DVC overwhelm states, which sustain that trauma-induced trance by downregulating body physiology, sometimes to minimal survival levels.

This trauma state creates what Dr. Peter Levine termed the ‘Trauma Vortex’. He states, “The interruption in the flow of one’s felt sense … becomes like a Vortex or whirlpool outside the main flow of the stream of consciousness. This vortex of energy is then maintained by traumatic symptoms so that some semblance of normal functioning can resume. The vortex orchestrates symptoms to prevent the organism from being overwhelmed by it, and also attempts through devices such as re-enactment, to reintegrate that energy into the large flow of experience.” (Levine, 1997)

Levine’s Somatic Experiencing (SE) utilizes a ‘pendulation’ of consciousness between the ‘Trauma Vortex’ and the counterforce of a ‘Healing Vortex’ in order to titrate the ANS charge from the nervous system. Similarly, Brent Baum’s Holographic Memory Resolution (HMR), Eye Movement Desensitization Repatterning (EMDR), Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT), and other somatic trauma therapies all utilize directed awareness through dialogue, movement, or energy-field techniques to discharge the pent-up ANS charge.

Through both intense single-event traumas and ongoing multi-event traumatic periods, the BMS establishes ‘short-cut’ pathways to more easily leap from SNS activation directly to DVC freeze/collapse states (bypassing T/T-1) when the felt-sense is similar to pre-existing traumas. All ‘similar’ trauma patterns are sorted internally and coupled to one another, reinforcing past trauma states.

Overwhelm – Dorsal Vagal Deactivation

Dorsal Vagal Complex (DVC) is never addressed by most outside-in bodywork modalities. They focus exclusively on frustrated Fight-or-Flight holding patterns within the tissue field.

We often talk about the Dorsal Vagal state as the Freeze/Collapse state, as if this is one single response, instead of two distinct systemic reactions to an overwhelming threat. When we perceive a challenge as life-threatening, with no chance to avoid a negative outcome, no possibility of escape or fight, and too big to handle alone, we prepare the BMS for death. This may entail immobilizing the musculoskeletal system, lowering physiological activity to the barest survival levels, numbing the nervous system, evacuating the bowel and bladder, and dissociating consciousness from the body.

It is the numbing and dissociating response that we find either systemically or locally in areas of the body associated with a particularly overwhelming event that is common to both Freeze and Collapse. In addition to traumatic or abusive life events, sudden falls and accidents, neglect/abandonment, extended contraction/compression states, as well as ALL surgeries, cause this type of overwhelm to body-consciousness.

Freeze

In Freeze, the breath is locked in a sharp inhale of sudden shock, that immobilizes the diaphragm. The tissue field becomes rigid and defensive, similar to a frustrated SNS Fight-or-Flight. The difference is that in SNS engagement, there is ‘power’ holding that pattern in place. By contrast, in Freeze, it’s as if we’ve constructed this immense, rigid fortress, then locked the door and ran away. The consciousness that animates form has ‘left the building’ so this area of solid tissue feels simultaneously rigid, and fragile or breakable. Most of us have had the experience of moving a certain way only to feel like something inside just might snap. Or during a bodywork session, we can’t fully relax because we’re afraid that the therapist might ‘break something off in there’. That’s DVC Freeze. The conscious Lifeforce that animates the body had to check-out because something happened that was too overwhelming/traumatic. Consequently, clients can be disconnected from their feelings, unable to feel anything, or unable to articulate how they feel.

The cause might have been a fall, accident, death of a loved one, or another type of sudden trauma. Often, Freeze is associated with an unexpected shock to the system that the body-mind doesn’t have the time or capacity to process.

Collapse

Collapse, on the other hand, is a state where the diaphragm is locked in an exhale, like we had the wind knocked out of us, and the structure simply crumbles. The BMS’s entire defense mechanism has been worn down over time to the point where there is no internal capacity to muster any adequate response. Here, the tissue field is flaccid, lax, and is missing any sense of vitality, consciousness, or animating Lifeforce. The felt-sense emotions of this area are utter despondency, failure, and overwhelm. When I make contact with an area of the body in DVC collapse, either my client, myself, or both of us will just feel like crying, which is inextricably tied to that moment of life where the only option was to ‘give up the ghost’.

In all states of DVC overwhelm, both Freeze and Collapse, consciousness dissociates from form to escape what it perceives as imminent death or potentially overwhelming pain, be that physical or psychoemotional. Always remember this is a ‘perceived’ threat that the BodyMind System doesn’t have the resources to meet in the moment—it can equally be an awkward social interaction, intense life stressor, or accidental trauma. Trauma is not an overwhelming event, it’s the PERCEPTION of an overwhelming event. It is an internal Felt-Sense experience that is so intensely unpleasant we have to escape by retreating beyond the physical body or into a deep inner refuge.

Collapse is often caused by extended traumatic events that wear down the system until it can’t take it anymore. This can be physical, mental, emotional, or sexual abuse, an unhealthy work or home environment, shame or ridicule, or any persistent traumatic situation. Here, the individual’s ability to mount a SNS defense has been eroded or undermined until the system’s only recourse is to collapse.

Sympathetic Bodyguard

Now the BMS never leaves itself completely unprotected, some nearby area is always taxed with ‘double-duty’. If the field of one of the vertebrae of the spine has collapsed making it hypermobile (too much movement), then the areas just above and/or below will become overly SNS defensive and restricted, making it hypomobile (too little movement). These two phenomena are directly related and can’t be addressed separately; only by opening a dialogue between them (through touch and/or body-centered counseling) can the areas of overwhelm remember they’re connected to the whole. In a typical Polarity Therapy contact, each of the therapist’s hands is on a different part of the client’s body, reminding it of its intrinsic interconnectedness.

Self-regulated VVC & DVC

When the vagal nerve pathways, anterior/Ventral and posterior/Dorsal self- or co-regulate (VVC and DVC), we are able to truly settle, sending our Energy back to the core to rest, digest, and rebuild healthy tissues. It upregulates the digestive organs and downregulates the heart, lungs, stress hormones, and muscle tone. By taking us out of hyper-vigilance, this quiets the mind and enables us to either fully engage with our outer world or direct our awareness inward to settle and meditate.

Our ability to ‘resource’ enables us to activate an appropriate response to our outside world, neither overcompensating with an over-active SNS nor under-compensating through an overwhelmed DVC Freeze or Collapse response. Our Sympathetic response is what keeps us from becoming overwhelmed, while our overwhelm response keeps us alive (physically or psycho-emotionally) when all else fails. Navigating away from overwhelm is VITAL for health.

Working Hypothesis and Protocol

Below is an outline of my working hypothesis for applying PVT more broadly to be incorporated into various bodywork therapies. This model begins with a fundamental understanding of PVT and an ability to recognize the signs and symptoms of each Polyvagal ANS state. The bodywork techniques are born out of these first two steps and can be adapted to different bodywork systems.

There are four additional considerations that hold true for all sessions, 1) First, assess the overall level of VVC coregulation/ease in the tissue field and the client’s ability to settle their BMS and relax, 2) then, assess areas of dysregulation to determine ANS state, defense mechanism(s), and extent of involved structures or whether it is a system-wide dysregulated engagement, 3) the therapist must settle their own system and ‘listen’ before any action is taken, returning to stillness and listening throughout the session, and finally 4) the therapist must honor the physical and energetic boundaries between themselves and the client. This protocol is at all times responsive and reflective, versus initiatory. In order to work with dysregulated ANS states the therapist must never impose their will on the client’s system, but instead, assist their BMS to navigate to safety and co-regulation from within. It is important to always remember that the ANS-endocrine-immune system complex is continuously assessing a person’s level of safety and enlisting a cascade of full-system physiological defenses to protect and keep them alive.

Ventral Vagal Complex (VVC) • Safety, Social NS

- ANS-Endocrine-Immune Pathways – Special efferent (motor) cranial nerves including myelinated Ventral Vagus pathway (CN-X) plus CN-V, VII, and IX. Sacral; Corticobulbar Tract; also afferent (inward/sensory) pathways in CNS.

A sophisticated set of responses supporting massive cortical development (i.e., enabling maternal bonding in the extended protection of vulnerable young and social cooperation via emotional expressiveness). These nerves operate involuntary actions of the face, voice, hearing, and related functions. Ventral Vagus also downregulates the heart and lungs to resting rhythms. Endocrine glands secrete ‘feel-good’ hormones like dopamine, oxytocin, serotonin, and endorphins, while the digestive and lymphatic systems are upregulated to support ingestion, digestion, assimilation, excretion, and increased immunity. - Signs & Symptoms – Relaxed alert state, characterized by a sense of safety (in the world, in the body, and with others). Capacity to engage socially with others, creating bonds of attachment, affection, love, and partnership. Physiological systems are functioning optimally. The tissue field and muscles are relaxed, mobile, and resilient; the breath and heart adopt a slow, steady rhythm including optimized HRV; and the mind is settled, enabling focused concentration and/or meditation. Expressive facial affect and vocal prosody. The ears are tuned to the range of the human voice and cues to affection and inclusion.

- Protocol(s) / Considerations – When VVC is the dominant ANS mode, it is important to support the continued sense of safety and peace. Gentle to moderate soothing bodywork manipulation supports this state. Active and passive range of motion (AROM & PROM) mobilizations can help free up minor, residual tension patterns. Gentle craniosacral, visceral, myofascial, energy, and nervous system mobilizations and balancing are all indicated.

SNS • Sympathetic Nervous System

- ANS-Endocrine-Immune Pathways – Thoracolumbar Sympathetic nerve ganglia innervating skeletal muscles of locomotion, particularly of the appendicular skeleton plus cervical, celiac, and mesenteric ganglia. A set of responses enabling mobility for feeding, defense, and reproduction via limbs and muscles. SNS nerves go to all visceral organs. They operate smooth muscles during daytime alertness and mobilization, and to the fight/flight responses.

Other bodily responses to SNS activation include pupil dilation, a grim or focused facial affect, monotone or strained voice, avoidance of direct eye contact, and hearing tuned to detect predatory sounds (very high or low frequencies, very loud or soft noises). There is an increase in heart-rate, blood pressure as well a blood clotting (for wound repair), and a decrease in our immune response. Saliva and digestive secretions are inhibited, as is the GI tract’s peristaltic motility and elimination of waste from the bladder and colon. SNS also decreases fat storage, burning it to fuel increased energy needs.

Additionally, the ANS-endocrine complex triggers stress hormones like epinephrine (adrenaline), norepinephrine (noradrenaline), and cortisol while the pancreas is stimulated the secrete glucose to fuel the crisis. The adrenal glands secrete activation and stress hormones; the pancreas secretes insulin; digestion and other ‘non-essential’ body functions are put on hold; the lungs dilate and heart races; and blood is being shunted away from the core, out to the big muscle groups of the limbs, neck and shoulders.

Biological changes start in the brain, where blood is drawn away from the neocortex to the limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis for instinctual responses. We become hypervigilant. There is no time to contemplate options, immediate action is required!

Dysregulated SNS • Frustrated Fight or Flight

- Signs & Symptoms – The tissue field is in contraction with standing muscle tension in specific areas associated with the catalyst stressors. The nervous system is holding onto an energetic charge causing the body to sustain a persistent tension of Fight in the upper body (shoulders, arms, hands, neck, chest). The psycho-emotional component of repressed Fight is anger, frustration, irritation, resentment, and rage.

We hold on to the Flight response as standing tension in low-back, psoas, butt, and legs we can’t run away from our problems. Psycho-emotionally, frustrated Flight shows up as things like worry, anxiety, fear, panic, or terror.

TMJ or jaw tension is another place the Fight response gets stored. Instead of doing battle with our fists, jaw tension is where we bite back a war of words. It suppresses that roar of frustration when we really want to give someone a piece of our mind but can’t or won’t.

The diaphragm and breath are held in an inhale, poised to release an explosion of activity. In dysregulation, the SNS can create dysfunctions in the GI tract, including indigestion, heartburn, cramps, and constipation.

NOTE: Fight can also show up in the lower body and flight in the upper. - Protocol(s) / Considerations – When SNS is dysregulated, you can use all of the same techniques as VVC. Here the client’s system is frustrated and challenged. It is oriented to pain and discomfort and the tissue field coils inward in contraction. Moderate to deep bodywork will bring the client’s body-consciousness to the specific areas of dysfunction/distress. It’s important to recognize that, this dysfunctional, painful Sympathetic pattern is keeping the client from dropping into DVC overwhelm. The bodywork manipulations should be minimally to tolerably uncomfortable. ’Pain’ and time must be in an inverse relationship. The more uncomfortable the manipulation the briefer it can be applied, the less uncomfortable, the longer. Once the client’s body-consciousness ‘shows up’ to meet the therapist’s hands, the therapist can begin to progressively soften their touch and ‘walk’ the system back to safety, relaxation, and co-regulation.

Rocking manipulations (from gentle to active) can be utilized to bypass and reset established nervous system holding patterns. All manipulations should be followed by gentle holds to rebalance the ANS.

Additionally, gentle visceral manipulation, addressing both the mobility and motility of visceral organs can aid the systems most directly affected by ANS dysregulation.

NOTE 1: It is important that the therapist initiate the letting go. If the client lets go first, there is a danger that their system simply succumbed to overwhelming force, ‘said uncle’, and dropped into DVC rather than relaxing. The goal is to shift the client’s internal perception from one of danger/threat to safety/peace.

NOTE 2: In dysregulated SNS, the client’s breath will be held in a sustained inhalation which also restricts tissue mobility and motility. It can be useful to instruct the client to breathe more deeply, and to utilize their exhale in the relaxation of the tissue field.

Hurts Good SNS • Combination Co- & Dyregulated

- Signs & Symptoms – The ‘Hurts Good’ state is a hypothetical state that lies between co- and dysregulated SNS which shares aspects of both. In this state, the client is simultaneously aware of the pain caused by a contraction in the tissue field impinging/activating nerve pain receptors (dysregulated SNS) as well as the underlying strength and capacity of their system to relax and release that tension (co-regulated SNS). It is invariably marked by the client commenting, something like, “Oh my God that hurts, but don’t stop!”

- Protocol(s) / Considerations – When SNS is in the ‘Hurts-Good’ state, you can use all of the same techniques as VVC and Disregulated SNS. Here the client’s system is simultaneously oriented to the pain/discomfort of the tissue field contraction, and also to its underly health, strength, vitality, and capacity. Here we have the extraordinary opportunity to help the client retrain their system’s response to challenging situations. The fundamental difference between the other two SNS states is whether mobilization happened within a framework of safety, creating a ‘can do’ attitude or minus that safety, creating a fear/defense response.

Just like dysregulated SNS, moderate to deep bodywork will bring the client’s body-consciousness to the specific areas of dysfunction/distress. It’s important to recognize that, this dysfunctional, painful Sympathetic pattern is keeping the client from dropping into overwhelm. The bodywork manipulations should at most be minimally to tolerably uncomfortable, at best completely pain-free. ’Pain’ and time must be in an inverse relationship. The more uncomfortable the manipulation the briefer it can be applied, the less uncomfortable, the longer. Once the client’s body-consciousness ‘shows up’ to meet the therapist’s hands, the therapist can begin to progressively soften their touch and ‘walk’ the system back to safety, relaxation, and co-regulation.

NOTE 1: It is important that the therapist initiate the letting go. If the client lets go first, there is a danger that their system simply succumbed to overwhelming force, ‘said uncle’, and dropped into DVC rather than relaxing. The goal is to shift the client’s internal perception from one of danger/threat to safety/peace. Always help the client orient away from overwhelm.

NOTE 2: In dysregulated SNS, the client’s breath will be held in a sustained inhalation which also restricts tissue mobility and motility. It can be useful to instruct the client to breathe more deeply, and to utilize their exhale in the relaxation of the tissue field.

Co-regulated SNS • Engaged Activation

- Signs & Symptoms – In co-regulated SNS we’ve nurtured a Ventral Vagal tone of safety, security, and interconnectedness; and conditioned ourselves to fluidly shift between SNS and VVC, activation-deactivation. Co-regulated SNS focuses us to achieve goals and motivates us to overcome obstacles. We draw strength and determination from it, and in partnership with VVC, it enables us to accomplish group objectives. It is a ‘can-do’ attitude that meets each obstacle as a fun personal challenge. We delight in our ability to play, create, compete, dance, and engage in sports/physical activity. Safe interaction with others also allows for intimate contact, sensuality, and sexuality.

- Protocol(s) / Considerations – When SNS is in a co-regulated state, you can use all of the same techniques as VVC. Here the system is orienting to its strength and full capacity, so all the SNS protocols apply. Additionally, deeper more active, and challenging manipulations may help the client achieve greater capacity and wellbeing.

NOTE: Athletes who are used to pitting themselves against external challenges have a far greater capacity to co-regulate their SNS. They have trained their systems to self- and co-regulate fluidly in intense situations. Still, always be on guard for engaging one of the system’s dysregulated defense strategies.

T-1 / T • Trauma Encoding • Turbulence

- ANS/Endocrine Pathways – T-1 and T are at the heart of the ‘Trauma Vortex’. Neurologically, here the ANS suddenly shifts gears between high adrenaline activation to complete DVC shutdown/immobilization. Picture an automobile going from 120-MPH to full-stop in a fraction of a heartbeat.

T, that traumatic trance-state, employs a containment process facilitated by the limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (LHPA Axis) in the brain, (which regulates the functioning of the ANS, the endocrine, and immune systems), as well as the ANS, endocrine, and immune systems. The LHPA stress response is the synthesis and secretion of glucocorticoids from the adrenal cortex. T is the instant the system pauses the perception of space-time and enters a self-induced trance where it encodes the moment of overwhelm. - Signs & Symptoms – T-1 (T minus 1) = T-1, the millisecond before Trauma encodes in the BM System, is indicated by an upwelling of overpowering emotions and/or pain which overwhelms the system. For that fraction of a moment, chaotic turbulence serges through the nervous system as the BMS scrambles for some unseen option, a physiological or defense mechanism to change the situation. This is often accompanied by uncontrollable trembling, twitching, numbness, dissociation, waves of full-body convulsions, sobbing, immobility, or paralysis. The most consistent signs, as the system shifts from T-1 to T, are numbness and dissociation.